“In Search of Wandering Spirit” - Alvin Elif Constant (1946-2006)

November 18, 2023, to January 20, 2023

Main Gallery

Featured Artist:

Alvin Elif Constant (1946-2006)

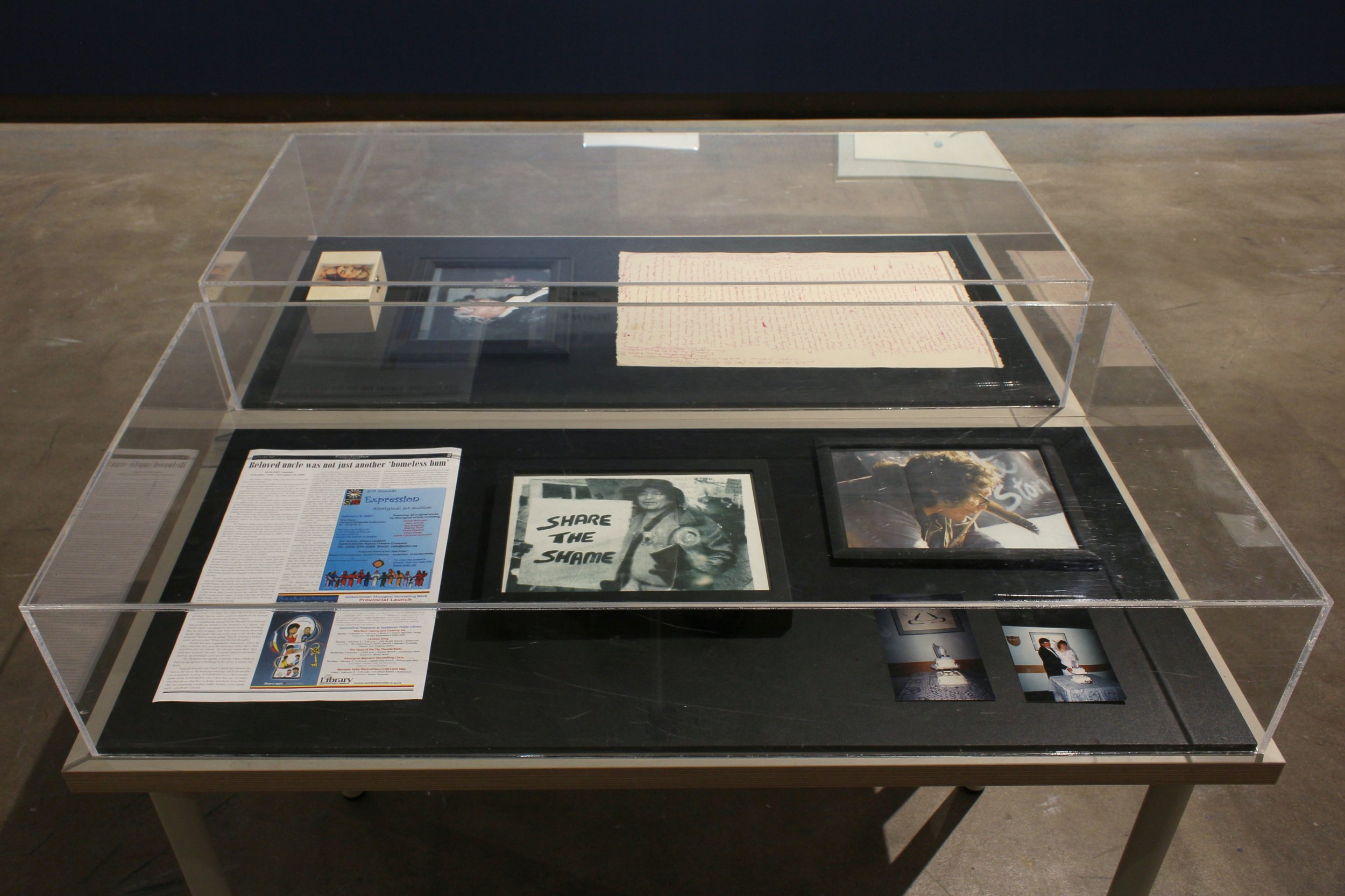

*PIctured, Constant protesting in support of the Lubican Indian Land Claims, during the Calgary Olympics. This picture made national news across the world.

Photo shared by Shelley Mike on Facebook, in a group in memory of Alvin.

Article Written by Paul Crawford

-

Reflecting on one's life, it's truly remarkable to trace those pivotal moments that set you on an unexpected path, shaping and defining your existence in ways you could never have anticipated. In my own life, one such transformative encounter unfolded in the early 1980s.

At the time, our family called West Vancouver home, and at twelve-years-old I was armed with the earnings from my paper route and on a mission to expand my collection, which I had been cultivating through the generosity of friends and relatives and a network of penpals from around the world. It was also about this time I learned of the hidden world of coin and stamp dealers, located just a quick bus ride away across the iconic Lions Gate Bridge, tucked away in the basement of Eaton's and scattered along bustling Hastings Street. While I was well aware that venturing across the bridge was undoubtedly off-limits, the allure of adventure and the potential rewards far outweighed any fears, doubts, and potential risks. I also knew that my secret would remain safe as long as I could make it back to Park Royal in time for the bus ride home.

The bus stop for my return journey was conveniently situated in front of the iconic Hudson Bay Building on West Georgia, nestled beneath the ample shelter of the grand awning that encircled the structure. It was here on one of these grand adventures where I had my first encounter with the artist known as "Wandering Spirit”. Shielded from the elements, Alvin would meticulously arrange his paintings on the sidewalk, his black portfolio boldly emblazoned with the words "Native Art," prominently displaying his price list. In the Middle of it all, Alvin sat cross-legged, meticulously crafting a painting right before our eyes. He exuded a commanding yet disarming presence, donning an easy smile and a kind disposition that welcomed interactions with all who passed by. I had never met anyone quite like him, and I was immediately enchanted by the man, his art, and I remained spellbound watching and listening to him as I awaited my bus to transport me back to the North Shore.

Aside from my elementary school art teacher, Alvin stands out as one of the very first "artists" I distinctly remember meeting. The memories of those moments spent observing him etched an indelible impact on me, an impact I could have never foreseen at the time. A decade later, our paths would serendipitously cross once again, this time in Victoria, where he could frequently be found selling his paintings on Government Street or along the Inner Harbour Causeway. During each of these encounters, I consciously took a moment to pause and watch Alvin as he painted, engaging in brief yet meaningful conversations while he diligently worked and generously shared his art with all those who passed by. Although our interactions were consistently brief and sporadic, Alvin's ability to remember me added an undeniably profound layer of significance to my connection with him. The memories of these moments have endured, resonating with me all these years later.

As the 1990s drew to a close, I moved away from the coast and my chance encounters with Alvin became a thing of the past. However, as the years passed, I frequently found myself reflecting on Alvin, bearing a deep regret for not seizing the opportunity to acquire one of his works during one of our visits. My profound admiration for his art remained unwavering, yet my hesitance to purchase one of his paintings was primarily rooted in the financial constraints of my student status at the time, and partially influenced by my lack of confidence in trusting my own artistic taste.

In 1993, I found myself presented with yet another unexpected opportunity one which would profoundly impact my journey. This opportunity arose when the owner of Gallery 1450 mysteriously vanished in the middle of the night, leaving both the building owner and all the affiliated artists in a challenging predicament. Up until that time Gallery 1450 had primarily served as a platform for showcasing the exceptional works of Indigenous Artists and with his sudden disappearance left many of these artists grappling with substantial losses. At the time, I was employed at Safeway, and it was there that I had developed a friendship with the gallery's landlord, Rachel Katz, who was a regular weekend shopper. She was aware of my deep interest in art, and when the gallery space was left vacant, she offered me the chance to run the gallery temporarily while they sorted out the mess and determined the space's future and over the next two years, I had the privilege of overseeing Gallery 1450.

Initially, my goal was to continue showcasing the work of Indigenous Artists. However, I quickly realized that many of the artists I encountered were not comfortable with the traditional Western gallery model of consigning their work. The gallery's previous owner's situation further underscored their concerns. Instead, these artists preferred to sell their work outright, with the business owner assuming both the risk and the reward. Consequently, I quickly realized why the work of Indigenous artists was more often confined to craft shops, failing to receive the recognition it rightfully deserved in mainstream commercial art galleries. As I reflect on that era and my subsequent experiences, I've also come to realize that the context of how and where you acquire something can significantly shape your perception of the object and ultimately become a determining factor in its inherent value.

A striking example of the impact of context occurred in 2013 when the renowned street artist Banksy set up a stand in New York City, offering his original artworks for a mere $60 each. It took several hours before the first sale was made in the middle of the afternoon to a woman who negotiated a 50% discount and bought two small canvases for her children. Another woman from New Zealand purchased two of the paintings, and a man from Chicago bought four, stating that he had recently moved and needed artwork for his walls. The total sales for the day amounted to a modest $420.

However, the story didn't end there. After Banksy authenticated the paintings, the woman from New Zealand consigned her two pieces to Bonham's Auctions in London, where they sold for a staggering total of £125,000.00. This anecdote highlights how the context and setting in which art is acquired can dramatically affect its perceived value.

Alvin Constant's story sadly mirrors the experiences of many Indigenous lives that were needlessly and tragically cut short. What struck me then and continues to resonate today is the overwhelming senseless tragedy that his story reflects, a tragedy deeply rooted in our colonial history.

Historically, most Indigenous artists had valid reasons not to trust the Western gallery model, where artists consigned their work. Instead, they preferred to sell their art as they produced it to Indigenous "craft" and "tourist shops," receiving cash and allowing these shops to set the prices based on market demand. However, this approach had several downsides. First, there are often little or no records of these artists' lives, making it challenging to tell their stories and document their legacies. Second, those who purchased their art didn't necessarily view it as "fine" art, diminishing its cultural value. Lastly, many of these artists led transient lives, which were often cut short, further disconnecting them from their communities.

Consequently, there are limited opportunities for art historians to study a comprehensive body of their work, showcase their art in major exhibitions, or ensure that their work is included in the collections of art museums. While there are exceptions, the majority of Indigenous artists remain unknown and unrecognized beyond their community, friends, and those fortunate enough to own their work.

I firmly believe that we need to make a conscious effort to bridge this gap in our collective art history, through the proper documentation and honoring of the lives and legacies of these artists. This is an essential step in recognizing their profound social and cultural contributions. This process would encompass acknowledging the significance of their art, documenting their lives and stories, while also firmly recognizing their place in the wider art world, beyond their immediate circles, and breaking away from long-established colonial narratives.

To that end, I am thrilled to introduce you to the life, art, and legacy of Alvin Elif Constant, also known as "Wandering Spirit" (1946-2006). If this is your first encounter with his work, I hope you experience the same sense of wonder and joy that I did when I first met him over 40 years ago. If you were fortunate enough to have met him and acquired one of his paintings, I hope you can share your stories, thoughts, memories, and any photos you may have, so we can better document his life and legacy. I also hope this exhibit can pave the way for many more such exhibitions and the concerted effort for us all to better document the lives and work of countless artists who left us far too soon, ensuring that their legacies are properly recorded and remembered before they are lost to us forever.

Born February 18, 1946, a son, brother, and the third youngest of 9 children born to Guy and Myrtle Constant, a residential school survivor and an Artist, Alvin Elif Constant was a Cree born on the James Smith Cree Nation, where he developed a passion for painting and drawing since he was a child.

Alvin attended the Gordons Indian Residential School in his younger years and later attended James Smith Day School in the neighbouring town of Kinistino, where he claimed he did “grade 13”. In the early 70’s, Alvin attended the Saskatchewan Indian Cultural College in Saskatoon and began doing some work with Artists in training. It was during this time that Alvin discovered the rich culture and traditions of his people. He was fascinated by the stories that the elders shared with him, stories of courage, wisdom, and humour. He felt a deep connection with his roots and a sense of belonging that he had never experienced before.

He dedicated his life to preserving and promoting his culture through storytelling and art, using his voice and imagination to inspire others.

Alvin moved away early in his teen years, hoping to pursue his dream of becoming a famous artist. However, life was not easy for him in the big city. He struggled to find a job, a place to live, and a way to support his art. He ended up being homeless, sleeping under bridges or in shelters and sketching portraits in bars or on the street for money or food. He never gave up on his art, though. He used whatever materials he could find, such as cardboard, paper bags, and newspaper, to create his paintings. He displayed his works on the sidewalks or in parks, hoping to catch the attention of passers-by. Sometimes, he sold some of his pieces for a few dollars, which he used to buy more supplies or food. He also met other homeless artists who shared his passion and vision. They formed a community of street artists who supported each other and exchanged ideas and techniques. His art was his way of expressing his feelings, struggles, and hopes. He wanted to show the beauty and the pain of living on the margins of society. He wanted to inspire people to see beyond appearances and stereotypes. He tried to make a difference with his art. ◆